When a drug has a narrow therapeutic index, even a tiny change in dosage can mean the difference between healing and harm. For drugs like warfarin, phenytoin, digoxin, and levothyroxine, the line between effective and toxic is razor-thin. That’s why generic versions of these medicines don’t get approved the same way as regular generics. They need something extra: bridging studies.

Why NTI Generics Are Different

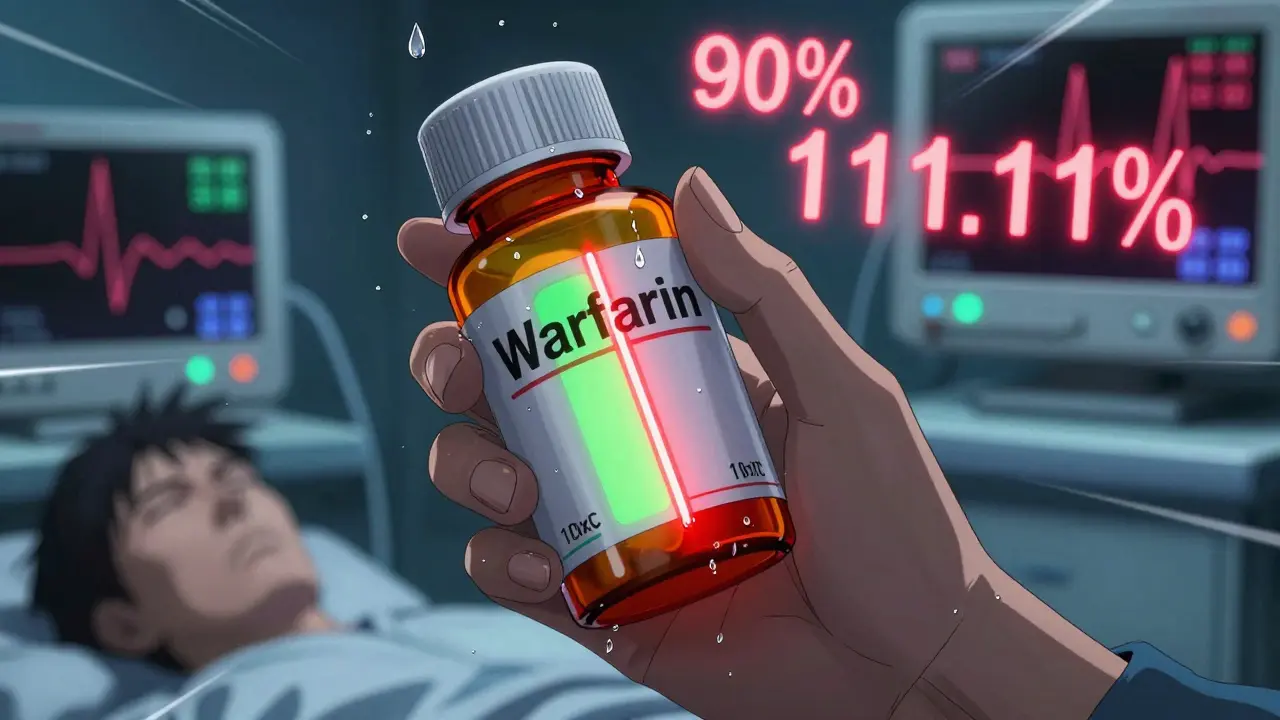

Not all generic drugs are created equal. Most generics only need to prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand-name version - meaning they deliver the same amount of drug into the bloodstream at roughly the same speed. For those, regulators accept a 80%-125% range for how much of the drug is absorbed. But for narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs, that range is too wide. A 20% difference in absorption could lead to a blood clot, a seizure, or heart failure. The FDA defines NTI drugs as those where the difference between the minimum effective dose and the minimum toxic dose is no more than two-fold. These drugs often require regular blood tests to monitor levels. Doses are adjusted in tiny increments - sometimes less than 20% at a time. That’s why a generic version that’s ‘close enough’ for a cholesterol pill isn’t close enough for warfarin.What Bridging Studies Actually Require

Bridging studies for NTI generics aren’t just bigger versions of standard bioequivalence tests. They’re more complex, longer, and costlier. Here’s what’s required:- Four-way crossover design: Each participant receives the brand drug twice and the generic drug twice, in random order. This means each person goes through four separate dosing periods, with washout periods in between.

- Reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE): Instead of a fixed 80%-125% range, the acceptable window shrinks based on how variable the original drug is. For NTI drugs, the 90% confidence interval for Cmax and AUC must fall between 90.00% and 111.11% - far tighter than for regular drugs.

- Stricter assay limits: The active ingredient in the generic must be within 95%-105% of the label claim. For non-NTI drugs, it’s 90%-110%.

Why These Studies Are So Hard to Run

Running a four-period crossover study isn’t just expensive - it’s logistically brutal. Participants have to come in four times, often over several months. Each visit requires fasting, blood draws every hour, and strict adherence to dosing schedules. Dropout rates are high. One study found that 15%-20% of volunteers quit before finishing, forcing companies to recruit even more people to compensate. Then there’s the data analysis. RSABE isn’t something you run in Excel. It requires specialized statistical software and experts who understand how to model within-subject variability. According to the FDA, only 35% of generic manufacturers have in-house teams trained to handle this. Many have to hire contract research organizations - adding more cost and delay. And even then, mistakes happen. Between 2018 and 2022, 37% of complete response letters from the FDA for NTI generics cited inadequate bridging study design as the main reason for rejection. That’s nearly three times higher than for non-NTI drugs.

Who’s Behind the Rules - and Why

The strict standards didn’t come out of nowhere. They were shaped by real-world harm. In the early 2000s, patients switching from brand to generic warfarin experienced unexpected bleeding events. Investigations showed small but clinically meaningful differences in absorption. The FDA responded by creating the RSABE method - a way to account for variability without letting unsafe products through. Dr. Lawrence Yu, former deputy director of the FDA’s Office of Pharmaceutical Quality, put it plainly: “The reference-scaled average bioequivalence approach was developed to account for the high variability sometimes observed with these critical drugs while maintaining appropriate stringency.” The European Medicines Agency agrees. In a 2022 position paper, CHMP stated that NTI drugs “require specific bioequivalence study designs and acceptance criteria that cannot be waived based on product similarity alone.” Even the International Generic and Biosimilar Medicines Association, which generally pushes for faster generic approvals, backs away from suggesting waivers for NTI drugs.The Market Reality: Fewer Generics, Higher Costs

Despite the huge demand for affordable medicines, NTI generics make up just 6% of all generic approvals between 2018 and 2022 - even though NTI drugs account for about 14% of all small-molecule medications. Only 18 NTI generics were approved in that time, compared to over 1,000 non-NTI generics. The result? Generic market share for NTI drugs sits at just 42%, while non-NTI generics dominate at 85%. That gap isn’t due to lack of need. It’s because the cost and complexity of bridging studies act as a massive barrier. Companies that try to enter this space often spend 3-5 years and tens of millions of dollars just to get one product approved. Teva Pharmaceuticals’ regulatory team says the four-period study design increases study duration by 40%-50% and doubles the number of subjects needed. That’s not just a technical hurdle - it’s a business decision. Many manufacturers simply avoid NTI drugs altogether.

Jon Paramore

December 22, 2025 AT 08:41RSABE for NTI drugs isn't optional-it's mathematically necessary. The 90-111.11% CI for Cmax/AUC isn't arbitrary; it's derived from within-subject variability models that account for pharmacokinetic noise. Most non-NTI generics rely on fixed bioequivalence thresholds, but that's statistically unsound for drugs with steep dose-response curves. The FDA's approach minimizes Type I error in high-risk scenarios. Period.

Swapneel Mehta

December 23, 2025 AT 18:12This is one of those posts that reminds you how much invisible work goes into making sure a pill doesn't kill you. The fact that these studies take 18 months and cost millions just to prove a generic is safe… it’s humbling. We take these drugs for granted until something goes wrong.

Ben Warren

December 25, 2025 AT 06:12It is patently absurd that any regulatory body would entertain the notion that physiologically-based pharmacokinetic modeling could supplant empirical human data for drugs with a two-fold therapeutic index. The biological variability inherent in human metabolism-gut transit time, CYP450 polymorphisms, hepatic first-pass effects-is not reducible to a computational simulation. To suggest otherwise is not only scientifically negligent, it is an affront to the principle of evidence-based medicine. The FDA’s caution is not bureaucratic overreach; it is the minimal ethical obligation owed to patients who rely on these agents for survival.

Teya Derksen Friesen

December 26, 2025 AT 09:08It’s inspiring to see how rigorous science can protect vulnerable populations. The fact that regulators didn’t just roll over for cost-cutting pressures speaks volumes. This isn’t about profit-it’s about precision medicine. We need more of this mindset across the pharmaceutical industry. Kudos to the teams running those grueling four-period crossovers. They’re the unsung heroes of safe pharmacotherapy.

Sandy Crux

December 28, 2025 AT 04:18…And yet… the FDA’s own data shows that 37% of NTI generic submissions are rejected due to flawed study design… which implies… that the very system meant to ensure safety is… statistically… flawed?… Or perhaps… overburdened?… Or… maybe… just… poorly implemented?…

Hannah Taylor

December 30, 2025 AT 00:55so like… are you telling me the fda just made up the 90-111% rule because they were scared of lawsuits? i mean, i switched my levothyroxine to a generic and felt fine… and now they want me to get blood drawn every hour? wtf. someone’s making bank on these studies. i bet the lab techs are getting paid in gold.

mukesh matav

December 31, 2025 AT 11:10Thank you for sharing this. It’s clear that the science behind these approvals is deeply thoughtful. I’ve seen patients struggle with switching generics, and now I understand why. I’ll be more careful in my practice moving forward.

Peggy Adams

January 1, 2026 AT 09:18They’re just making this up to keep prices high. Generic companies can’t afford these studies, so they don’t even try. That’s why you’re stuck paying $500 for a 30-day supply of warfarin. Big Pharma’s got the FDA in their pocket. Wake up.