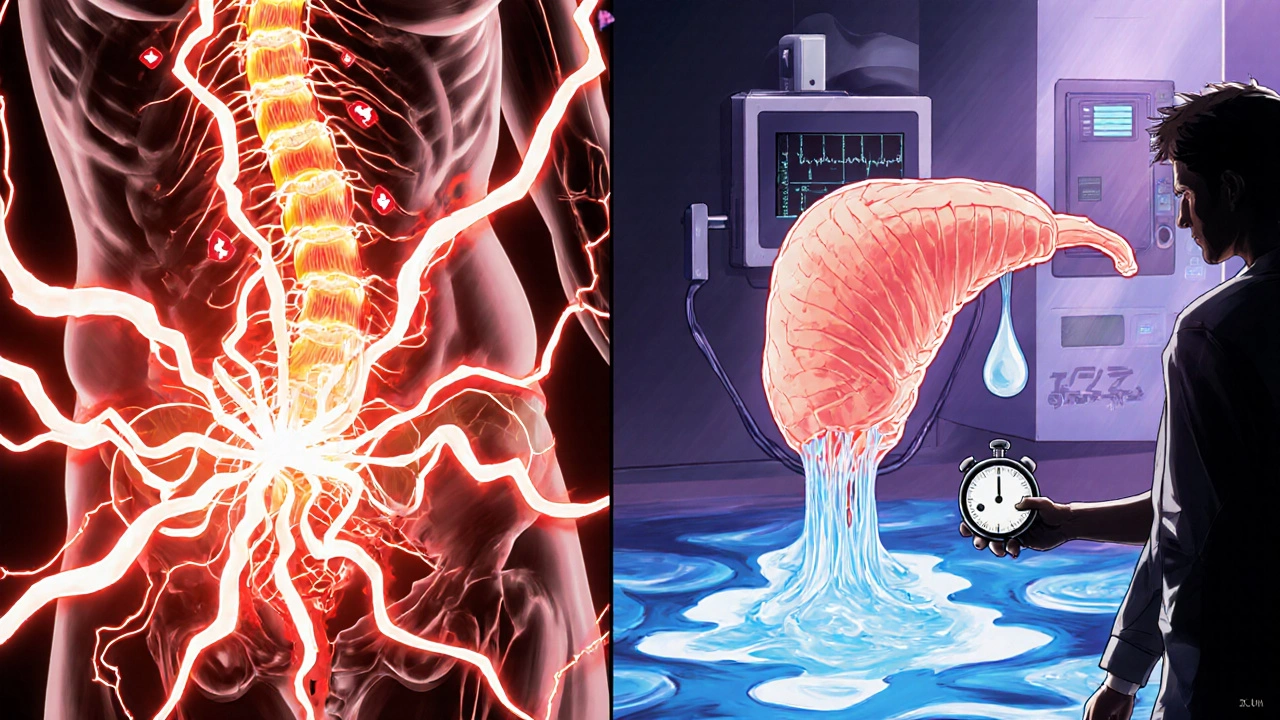

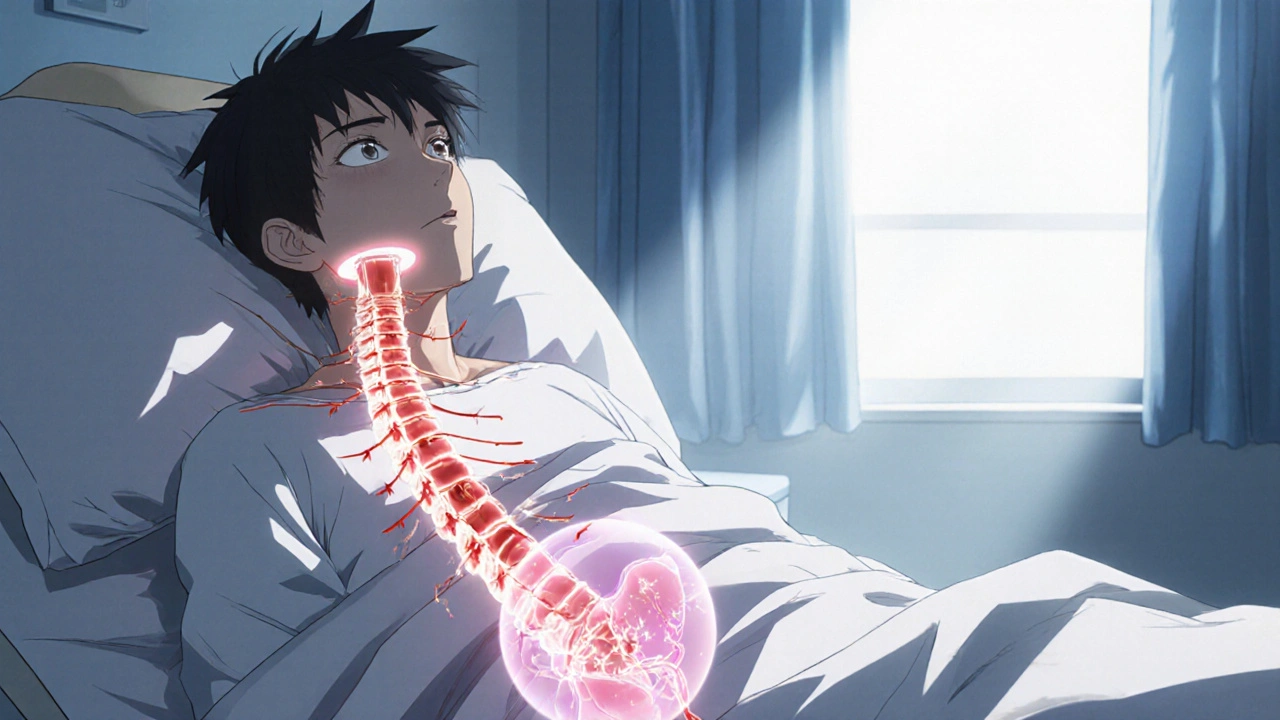

Imagine waking up after an accident and discovering you can’t control when you need to pee. For many people living with a spinal cord injury, that scenario is a daily reality. The link between the spinal cord and the bladder is a finely tuned nervous system, and when the cord’s signal pathway is damaged, the bladder’s behavior changes dramatically. This guide breaks down exactly why those changes happen, what symptoms show up, and how doctors and patients can manage the problem.

Neural control of the bladder: the basics

The bladder works like a smart storage tank. As it fills, stretch receptors in the bladder wall send signals up the spinal cord to the brain. When the storage limit is reached, the brain sends a “let‑go” command back down the same pathway, relaxing the sphincter muscles and contracting the detrusor muscle to empty urine. Two critical neural circuits are involved:

- Upper Motor Neuron pathway - carries impulses from the brain to the sacral spinal cord (S2‑S4) and then to the bladder.

- Lower Motor Neuron pathway - directly innervates the detrusor and external sphincter from the sacral cord.

If either of these routes is disrupted, the bladder can become over‑active, under‑active, or completely uncoordinated.

How spinal cord injury rewires bladder function

When a spinal cord injury (SCI) occurs, the damage can be classified as complete or incomplete, and it can happen at any level of the cord. The level matters because it determines which neural circuits stay intact.

Below the injury level, the sacral reflex arc may still work, but the brain can no longer modulate it. That creates what clinicians call “neurogenic bladder,” a condition where the bladder’s behavior is driven by reflexes rather than conscious control.

Two main patterns emerge:

- Upper motor neuron (spastic) bladder - Usually follows injuries above the sacral region. The detrusor muscle becomes over‑active, contracting suddenly and often before the bladder is full. This leads to urgency, frequency, and urge incontinence.

- Lower motor neuron (flaccid) bladder - Typically seen with injuries at the sacral level or cauda equina damage. The detrusor loses its contractile power, causing incomplete emptying, large residual volumes, and overflow incontinence.

Both patterns can coexist in the same person, especially if the injury is incomplete.

Urinary incontinence symptoms after SCI

Incontinence isn’t a single symptom; it can show up in several ways, each pointing to a different underlying bladder problem.

- Urge incontinence - A sudden, overwhelming need to void that can’t be delayed. Common in spastic bladders.

- Stress incontinence - Leakage during coughing, sneezing, or physical exertion. Less common after SCI but may appear if pelvic floor muscles are weakened.

- Overflow incontinence - Dribbling that occurs when the bladder is constantly over‑filled. Signals a flaccid bladder with poor emptying.

- Nocturnal enuresis - Bedwetting that may persist long after the injury.

Patients often report a mix of urgency, frequency (up to 12-15 voids a day), and incomplete emptying, which together increase the risk of urinary tract infections (UTIs) and stone formation.

Diagnostic tools: how doctors pinpoint the problem

Accurate diagnosis starts with a thorough history and physical exam, but the real insight comes from specialized tests.

Urodynamic Study measures bladder pressure, compliance, detrusor activity, and sphincter coordination during filling and voiding phases. It tells clinicians whether the bladder is spastic, flaccid, or a hybrid.

Additional tools include:

- Renal ultrasound - checks for hydronephrosis caused by high residual volumes.

- Post‑void residual (PVR) measurement - a simple bladder scan that quantifies how much urine is left after a void.

- Cystoscopy - visual inspection of the bladder lining, useful when recurrent infections or stones are suspected.

These tests guide the treatment plan, ensuring that interventions target the specific bladder pattern present.

Management strategies: from lifestyle tweaks to surgery

Managing neurogenic bladder after SCI is a step‑by‑step process. The goal is to protect the upper urinary tract, achieve social continence, and maintain quality of life.

1. Behavioral and timing techniques

Even with impaired neural control, a regular voiding schedule helps reduce bladder over‑distension. Patients may set a timer to attempt voiding every 2-3 hours, combined with double‑voiding to lower residual volume.

2. Medications

- Anticholinergics (e.g., oxybutynin, solifenacin) - calm an over‑active detrusor in spastic bladders.

- Beta‑3 agonists (mirabegron) - relax the bladder muscle without the dry‑mouth side effect of anticholinergics.

- Alpha‑blockers - lower urethral resistance, useful when outlet obstruction contributes to retention.

Medication choice depends on the bladder pattern identified in urodynamics.

3. Catheterization

When the bladder can’t empty on its own, clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) becomes the gold standard. The patient inserts a sterile catheter every 4-6 hours, empties the bladder, and then removes the catheter. CIC minimizes infection risk compared with an indwelling Foley catheter.

If CIC isn’t feasible (e.g., limited hand function), a suprapubic catheter may be placed under local anesthesia. Long‑term catheter users need regular monitoring for UTIs and bladder stones.

4. Electrical stimulation and nerve modulation

Emerging therapies include sacral neuromodulation and tibial nerve stimulation. These techniques aim to restore some voluntary control by re‑training the reflex pathways.

5. Surgical options

- Bladder augmentation (enterocystoplasty) - adds a segment of intestine to increase bladder capacity and compliance.

- Artificial urinary sphincter - implanted device that squeezes the urethra closed, useful in severe stress incontinence.

- Urinary diversion - creates a completely new pathway for urine, reserved for cases where the bladder can’t be salvaged.

These are considered only after conservative measures have failed.

Living with a neurogenic bladder: practical tips

Beyond medical treatment, everyday habits make a huge difference.

- Stay hydrated but avoid excessive caffeine or alcohol, which irritate the bladder.

- Maintain proper perineal hygiene - washing with mild soap after each void reduces bacterial colonization.

- Schedule regular follow‑ups: urodynamics every 1-2 years, renal ultrasound annually, and urine cultures as needed.

- Consider a bladder diary - tracking fluid intake, void times, and incontinence episodes helps clinicians spot patterns.

- Wear protective pads and plan bathroom access in public places to reduce anxiety.

With a proactive approach, most people with SCI achieve continence levels that allow work, travel, and social activities.

Future directions: research and technology

Scientists are exploring stem‑cell grafts to restore damaged spinal pathways, and implantable bio‑sensors that continuously monitor bladder pressure. While still experimental, these innovations could someday replace the need for catheters or chronic medication.

Why does a spinal cord injury cause urgency rather than just inability to void?

In injuries above the sacral region, the brain loses control over the reflex‑driven detrusor muscle. The bladder still sends stretch signals, but without higher‑order inhibition the sacral reflex fires prematurely, creating a sudden urge to empty even when the bladder isn’t full.

Is clean intermittent catheterization safe for people with limited hand function?

Yes, most patients use adaptive devices such as catheter holders or voice‑activated tools. Training with an occupational therapist can make CIC a reliable, low‑infection option.

How often should urodynamic studies be repeated?

Typically every 1-2 years, or sooner if new symptoms arise (e.g., worsening incontinence, recurrent UTIs, or changes in renal imaging).

Can medications alone control urinary incontinence after a spinal cord injury?

Medications help, especially anticholinergics for spastic bladders, but most patients also need bladder training, timed voiding, or catheterization to achieve reliable continence.

What are the biggest long‑term risks if neurogenic bladder isn’t properly managed?

Chronic kidney damage from high bladder pressures, recurrent urinary tract infections, bladder stones, and reduced quality of life are the main concerns.

Vikas Kumar

October 23, 2025 AT 16:34Our nation must prioritize funding for spinal injury research.

Celeste Flynn

October 31, 2025 AT 03:34Neurogenic bladder isn’t just about leaks; it’s a sign that the reflex arc is out of sync. Monitoring post‑void residuals gives a quick snapshot of how well the bladder empties. A simple bladder scan every few months can catch rising volumes before they damage the kidneys. Pair that with a bladder diary and you’ll have actionable data for the urologist. Early intervention often means fewer infections and a better quality of life.

kenny lastimosa

November 7, 2025 AT 15:34When the nervous system loses its top‑down command, the body reveals its own autonomy. The bladder, once a passive reservoir, becomes a reflexive actor driven by sacral circuits. This shift forces us to rethink control as a partnership rather than a hierarchy. Patients often experience a paradox: the urge appears early, yet the ability to finish is compromised. Such duality mirrors broader philosophical questions about freedom within constraint. Understanding this helps clinicians tailor interventions that respect residual reflexes. Ultimately, embracing the bladder’s new voice can reduce frustration and improve outcomes.

Heather ehlschide

November 15, 2025 AT 03:34Intermittent catheterization restores bladder emptying without a permanent tube. It’s best performed every 4‑6 hours, using a sterile catheter each time. For those with limited hand function, adaptive holders or voice‑activated devices can make the process manageable.

Shan Reddy

November 22, 2025 AT 15:34Staying hydrated is key, but swapping soda for water can cut irritation dramatically. Gentle perineal cleaning with mild soap after each void cuts bacterial load. Setting a timer for a regular voiding schedule keeps the bladder from over‑distending.

CASEY PERRY

November 30, 2025 AT 03:34The detrusor overactivity observed in spastic neurogenic bladder reflects hyper‑reflexic sacral firing. Anticholinergic agents mitigate this by antagonizing muscarinic receptors. Dose titration should balance efficacy with cognitive side‑effects.

Naomi Shimberg

December 7, 2025 AT 15:34Nevertheless, the rush to implant neuromodulators often sidesteps long‑term safety data, a fact seldom highlighted in optimistic press releases.

Kajal Gupta

December 15, 2025 AT 03:34Think of your bladder like a balloon at a party-if you keep inflating it without a release valve, eventually it will pop or leak. Adding a little magnesium‑rich diet can calm the muscle’s over‑excitability. Learning simple pelvic floor exercises, even with limited mobility, adds another layer of control that many overlook.

Zachary Blackwell

December 22, 2025 AT 15:34The mainstream medical narrative tells us that technology will soon solve every bladder problem, but the reality is far murkier. Hidden behind glossy conference slides are undocumented complications that patients rarely discuss. For instance, the purported “miracle” of sacral neuromodulation often masks a steep learning curve and unexpected hardware failures. Manufacturers conveniently downplay the fact that some devices emit electromagnetic fields that could interfere with everyday electronics. Moreover, the data sets used to justify widespread adoption are frequently funded by the same companies that profit from the implants. When you dig into the peer‑reviewed literature, you’ll find a handful of small studies with optimistic endpoints but scarce long‑term follow‑up. This selective reporting creates a feedback loop where clinicians feel pressured to prescribe the newest gadget rather than consider low‑tech alternatives. Meanwhile, patients are left juggling costly maintenance visits, battery replacements, and the ever‑looming risk of infection. The conspiracy isn’t a grand illusion; it’s a systematic bias that privileges profit over patient autonomy. Even the regulatory agencies, tasked with safeguarding the public, are often understaffed and rely on industry‑submitted data. As a result, many subtle adverse events slip through the cracks until they become a public health concern. I’ve spoken to several individuals who experienced device migration that required invasive revision surgery, yet their stories rarely make headlines. If you examine the raw numbers, the success rate drops dramatically after the first two years, contradicting the perpetual optimism marketed to caregivers. So before you jump on the hype train, ask yourself whether a simple clean intermittent catheter schedule might serve you just as well without the hidden costs. In the end, staying informed and skeptical protects you from becoming another statistic in a profit‑driven agenda.

prithi mallick

December 30, 2025 AT 03:34i totally get the feeling you described it’s like your body is speaking a new language. Embracing that change can be scary but also empowering. try to listen to those early urges as cues, not annoyances. a little coaching can turn that reflex into a useful rhythm. remember, patience is key – progress may be slow but steady. you’re not alone in this journey, and every step forward matters.

Michaela Dixon

January 6, 2026 AT 15:34Exploring the landscape of neurogenic bladder feels like mapping an uncharted continent where each symptom is a landmark on a foggy horizon. The urgency you feel may be mistaken for panic, yet it actually signals the sacral reflex arcs shouting for attention. By keeping a meticulous bladder diary you turn those vague sensations into concrete data points that guide therapeutic choices. Hydration habits, while essential, must be balanced against bladder irritants like caffeine that can turn a gentle tide into a storm. The interplay between anticholinergic medication and lifestyle tweaks creates a dance that, when choreographed correctly, can restore a semblance of normalcy. Even the most advanced surgical options, such as augmentation, are just one movement in this complex routine. So, patience, observation, and open communication with your care team form the tripod that steadies the whole expedition. Ultimately, the goal isn’t just continence, but reclaiming confidence in everyday moments.

Dan Danuts

January 14, 2026 AT 03:34Great insight! Keep that diary handy and share it at each appointment – it’s a powerful tool. Celebrate tiny wins like a smoother voiding schedule, they add up. Remember, consistency beats perfection every time.

Dante Russello

January 21, 2026 AT 15:34Indeed, the disciplined approach, coupled with regular monitoring, not only fosters confidence, but also provides clinicians with invaluable metrics, enabling timely adjustments, and ultimately preserving renal function, which is paramount to long‑term health.

James Gray

January 29, 2026 AT 03:34Yo! staying positive while tackling bladder issues can really boost recovery vibes. Keep the humor alive, it makes the routine less of a chore.

Scott Ring

February 5, 2026 AT 15:34Absolutely, a light‑hearted attitude combined with diligent care creates a balanced mindset. It’s all about finding that sweet spot between seriousness and fun.