Every year, over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. They’re cheaper, just as effective for most people, and save the healthcare system billions. But sometimes, a doctor says: no. Not this time. I need the brand name. Why? And how do they make that happen?

It’s called a prescriber override. It’s not a loophole. It’s not a preference. It’s a legally recognized tool that lets physicians block generic substitution when clinical safety is at stake. But here’s the problem: most doctors don’t know how to use it right. And when they mess it up, patients pay the price-with bad reactions, hospital visits, or worse.

How Generic Substitution Works (And When It Doesn’t)

When you walk into a pharmacy with a prescription for a drug like levothyroxine or warfarin, the pharmacist doesn’t just hand you whatever’s cheapest. They check if there’s a generic version approved by the FDA. If there is, and your state allows it, they’re supposed to swap it in-unless the doctor says otherwise.

This system was built on the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. It gave drug companies patent protection for brand-name drugs while creating a fast track for generics. The goal? Lower costs without sacrificing safety. And it worked. Between 2010 and 2019, generics saved the U.S. healthcare system $2.2 trillion.

But not all drugs are created equal. Some have what’s called a narrow therapeutic index. That means the difference between a helpful dose and a dangerous one is tiny. A little too much? Seizures. A little too little? Blood clots. For drugs like phenytoin, carbamazepine, or levothyroxine, even small differences in inactive ingredients-like fillers or coatings-can throw off how the body absorbs the medicine.

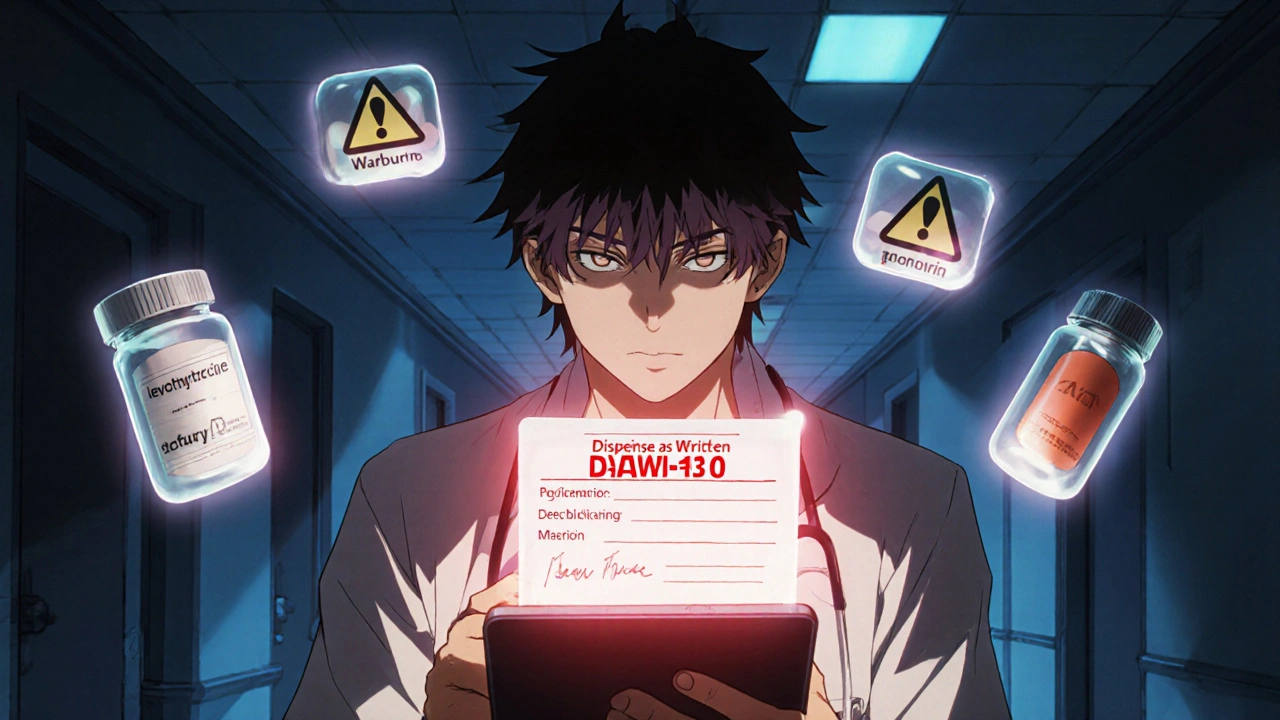

That’s where prescriber override comes in. It’s the legal backstop. If a doctor believes switching to a generic could hurt a patient, they can write “Dispense as Written” or use a DAW-1 code on the prescription. That tells the pharmacy: don’t substitute. Give the brand.

The DAW-1 Code: What It Really Means

The key to a valid override isn’t just saying “no generics.” It’s using the right code. The National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) created nine DAW codes to standardize how prescriptions are processed electronically. DAW-1 is the one that matters here: “Substitution Not Allowed by Prescriber.”

But here’s where things go wrong. In some states, you need to write “Brand Medically Necessary” by hand. In others, you just check a box in your electronic health record. In Massachusetts, “No Substitution” works. In Oregon, you can even call it in. But if your EHR system defaults to “DAW-3” (pharmacist chooses generic) and you forget to change it? The pharmacy will dispense the generic-even if you meant to block it.

A 2022 survey of 1,247 physicians found that 41% struggled because their EHR templates didn’t match their state’s rules. Another 37% said pharmacies often ignored their override requests. One doctor in a Reddit thread described a patient who went into thyroid storm after a pharmacy substituted levothyroxine-even though the prescription had DAW-1. The system failed. The patient almost died.

State Laws Are a Patchwork-And It’s Dangerous

There are 50 states. Each has its own rules. That’s not a bug. It’s a feature of U.S. healthcare. But for doctors who practice in multiple states-or for patients who move-it’s a nightmare.

Illinois? You have to mark a box labeled “May Not Substitute.” Kentucky? You must write “Brand Medically Necessary” in your own handwriting. Michigan? You need to write “DAW” or “Dispense as Written.” California? You need “Brand Medically Necessary” plus your signature. Texas? Two-line prescription format only.

And it’s not just about writing. The FDA’s Orange Book is the official list of drugs considered therapeutically equivalent. Pharmacists are supposed to use it to decide what’s substitutable. But 42 states legally require it. The rest? They just use it as a guideline. So one pharmacist in Florida might think two generics are interchangeable. Another in New York might not. And the doctor? They have no idea which rules apply until the patient comes back with a bad reaction.

According to the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, 27 states let pharmacists substitute without telling the patient first. That’s called presumed consent. In those places, the override burden falls entirely on the doctor. If you don’t write it right, the generic goes out-and you’re the one who gets blamed.

When Overrides Are Necessary (And When They’re Not)

There are three real medical reasons to override:

- Narrow therapeutic index drugs - Levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, lithium, cyclosporine. Even small absorption differences can be deadly.

- Documented failure with generics - If a patient had a seizure after switching to a generic carbamazepine, the next prescription must be brand.

- Allergies to inactive ingredients - Some generics use different dyes, fillers, or preservatives. If a patient reacts to lactose or FD&C yellow dye in a generic, the brand might be the only safe option.

But here’s the truth: most overrides aren’t for these reasons. A 2019 study found DAW-1 use was highest in anticonvulsants (14.8%) and psychiatric meds (12.3%)-where clinical data shows little real difference between brands and generics. Why? Because doctors are afraid. They’ve heard stories. They don’t trust the generic. Or worse-they don’t know the difference.

Dr. William Shrank from UnitedHealth Group found that physicians often overestimate how much formulation changes matter. In one study, only 58% of doctors correctly understood their own state’s override rules. A quarter said they accidentally let substitutions happen because they didn’t realize their EHR was defaulting to generic.

And the cost? DAW-1 prescriptions cost 32.7% more on average. In 2022, inappropriate overrides added $7.8 billion in unnecessary spending. Express Scripts found that 18.4% of brand-drug spending they paid for came from DAW-1 codes that shouldn’t have been there.

How to Get It Right

If you’re a doctor, here’s what you need to do:

- Know your state’s law. Go to the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy website. They have an interactive map updated every quarter. Don’t guess. Don’t rely on memory.

- Use your EHR correctly. Make sure your template has the right DAW-1 option. If it doesn’t, ask your IT team to fix it. If they won’t, print a sticky note with your state’s requirement and tape it to your monitor.

- Write it clearly. Don’t say “no generics.” Say “Dispense as Written” or “Brand Medically Necessary” - exactly as your state requires.

- Document the reason. If a patient had a bad reaction to a generic, write it in the chart. “Patient experienced tremors and elevated INR after switch from brand to generic warfarin.” That’s your defense if a pharmacy questions it.

- Check the Orange Book. Before you override, ask: is this drug even eligible for substitution? Some drugs don’t have a generic at all. Others have generics with a “B” rating-meaning they’re not considered equivalent. You don’t need to override those.

Clincs that use standardized override checklists and EHR templates reduced medication errors by 42.3% in one Michigan study. That’s not magic. That’s process.

What’s Next?

There’s a bill in Congress called the Standardized Prescriber Override Protocol Act. It would create one national rule. No more state-by-state confusion. But until then, the burden stays on you.

Electronic prescribing is getting better. By late 2024, the NCPDP will embed override rules directly into the e-prescribing standard. That means your EHR might soon auto-fill the right code based on your location. But for now? You’re still the gatekeeper.

Prescriber override isn’t about resisting generics. It’s about protecting patients when the system isn’t enough. Use it wisely. Use it correctly. And never assume someone else will catch your mistake.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a pharmacist override a prescriber’s DAW-1 request?

No. Once a prescriber uses DAW-1, the pharmacy is legally required to dispense the brand-name drug. Even if the insurance company denies payment or the pharmacist thinks it’s unnecessary, they cannot substitute. The override is binding under state law.

Do I need to write a note in the patient’s chart for every override?

It’s not always required by law, but you should. If a patient has a bad reaction after a substitution you didn’t block, your chart note is your only defense. Document the clinical reason: “Patient experienced seizure after generic phenytoin switch. Brand required for therapeutic stability.” That’s not just good practice-it’s legal protection.

Why do some pharmacies ignore DAW-1 requests?

Sometimes it’s a system error-EHRs miscode the prescription. Other times, pharmacists don’t recognize the notation because it’s not written in their state’s exact wording. In 68% of override-related claim rejections, the issue was improper documentation. Always use your state’s exact language. If you’re unsure, call the pharmacy ahead of time to confirm what they accept.

Can I override for a patient who just prefers the brand?

No. DAW-1 is only for medical necessity. If a patient wants the brand because they believe it’s better, that’s not a valid override. But if they’ve had a documented adverse reaction to a generic, then yes. Some patients will ask. Politely explain the rules: “I can only block generics if there’s a clinical reason. Otherwise, we’re required to use the cheaper option to save costs.”

Are there any drugs that can never be substituted, even without a DAW-1?

Yes. Some drugs don’t have FDA-approved generics at all. Others have generics with a “B” rating in the Orange Book, meaning they’re not considered therapeutically equivalent. For example, some extended-release formulations or complex biologics fall into this category. You don’t need to override those-the system already blocks substitution automatically.

Chris Taylor

November 28, 2025 AT 05:05My grandma switched to generic levothyroxine and started having heart palpitations. Took three weeks and three ER trips to figure out it was the generic. Doctors never told us to check the brand. Now I print out that DAW-1 chart and tape it to my fridge.

Sean Slevin

November 29, 2025 AT 01:27So… let me get this straight… we have a system that saves billions… but if you don’t write ‘Dispense as Written’ in exactly the right way… someone might die? And the pharmacist doesn’t even have to tell you they swapped it? That’s not healthcare… that’s Russian roulette with pills…!!!

Melissa Michaels

November 29, 2025 AT 05:51The data is clear: 41% of physicians struggle with EHR templates. This isn’t a failure of individual doctors-it’s a failure of system design. We need mandatory EHR certification standards tied to state override rules. No more guesswork. No more patient harm. This is fixable with policy.

Nathan Brown

November 29, 2025 AT 14:11It’s funny how we trust algorithms to drive our cars but won’t trust them to dispense our medicine. We’ve automated everything except the one thing that should be most precise-dosing. The fact that a doctor in Texas has to write a two-line prescription while a doctor in Oregon can just say it out loud… that’s not healthcare. That’s chaos with a stethoscope.

Olivia Currie

November 30, 2025 AT 07:41OH MY GOD. I just realized I’ve been writing ‘no generics’ for years. I thought that was enough. I’m so sorry to every patient I might’ve put at risk. I’m going to the NABP website right now. This changed everything.

Curtis Ryan

November 30, 2025 AT 20:17generic are fine unless you're one of those people who gets all weird after switching. i mean come on. i took generic advil for 10 years and never had an issue. why are we making this so complicated?

Rajiv Vyas

December 1, 2025 AT 18:27Big Pharma paid off the FDA to make generics look safe. The real reason doctors override? Because the brand has extra chemicals that make you addicted. They want you hooked on $200 pills. The Orange Book? A lie. The government is lying to you. Always.

farhiya jama

December 2, 2025 AT 10:04Why am I even reading this? I just want my cheap meds. If I die because I got the wrong pill… whatever. I’m not paying for someone’s ego.

Astro Service

December 2, 2025 AT 19:36Generic drugs are a communist plot to weaken America. We built the greatest healthcare system on earth with brand names. Why are we letting foreigners make our pills? This is why we lost the war on drugs.

DENIS GOLD

December 3, 2025 AT 03:43So the solution to doctors being dumb is… more paperwork? Brilliant. Just like how we fixed the economy-with more forms. I bet if we made them write it in cursive while standing on one foot, they’d get it right.

Ifeoma Ezeokoli

December 3, 2025 AT 18:12Back home in Nigeria, we just use what’s available. If the pill works, it works. If it doesn’t, we go to the next clinic. Maybe we don’t need all this tech and codes. Maybe we just need more doctors who listen.

Daniel Rod

December 4, 2025 AT 02:49Imagine if every time you switched phone chargers, your phone exploded. That’s what we’re doing with meds. We treat pills like they’re interchangeable… but they’re not. We need a universal standard. And we need it yesterday. 🙏

gina rodriguez

December 4, 2025 AT 13:56I love how this post breaks it down so clearly. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen patients suffer because of this. Thank you for giving us the tools to do better. I’m printing this out for my whole team.

Sue Barnes

December 6, 2025 AT 02:46Any doctor who doesn’t know how to use DAW-1 shouldn’t be prescribing. That’s malpractice waiting to happen. This isn’t complicated. It’s basic. If you can’t do your job, get out of the way.

jobin joshua

December 7, 2025 AT 21:08Bro I just clicked DAW-1 and forgot to check the box. My patient got the generic. I’m so sorry. 😭

Matthew Stanford

December 8, 2025 AT 04:59Hey, thanks for sharing that. I’ve been there too. I think the real issue isn’t the doctors-it’s that pharmacies don’t have a simple way to flag override risks. We need a push notification in the system when a DAW-1 is missing. Not a wall of state rules. Just one alert. That’s all.